By Amanda Ruehlen

UNC Web Editor

the Durham VOICE

thedurhamvoice@gmail.com

There’s always work at the post office.

But proving this old adage about the U.S. Postal Service has not been easy for African-Americans.

Philip Rubio, a professor at North Carolina A&T State University and a former letter carrier in Durham, gave an overview of his new book, “There’s Always Work at the Post Office: African-American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality,” at the Hayti Heritage Center on Sunday afternoon.

“This is an ongoing process, and it’s a story of stories that never ends,” Rubio said in his presentation. “I’m just scratching the surface in this book.”

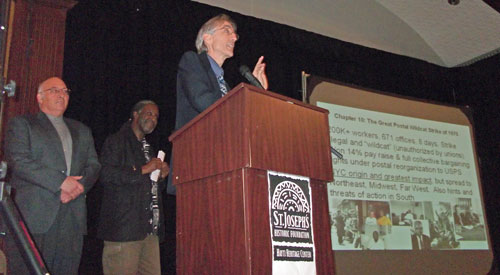

Philip Rubio discusses his book about African-American postal workers and their fight for equality in the postal service on Sunday at the Hayti Heritage Center. Behind him stand two other guest speakers and former postal workers, Richard Koritz and Ajamu Dillahunt. (Staff photo by Amanda Ruehlen)

Rubio’s book tells the neglected story of black postal workers and the critical role they played in labor and black freedom movements from 1940 to 1971. He said tracing this story reveals the significance of postal jobs to black community development.

“It was a steady job, and your pay was the same regardless of where you worked in the country,” Rubio said. “But it went farther in the South, in small cities and in the black community.”

He described the post office as a unique opportunity because it was a working-class job that provided middle-class status.

In 1940, postal workers were in the top 5 percent of the black wage distribution, Rubio said. He added that the top 14 percent of all blacks in the middle class worked for the postal service.

“The pay, the benefits and job security allowed [African-Americans] to accumulate wealth, provide higher education for themselves and their children, and to be social activists,” he said.

But despite these perks, Rubio said it was a double-edged sword for blacks working at the post office.

In 1949, Ebony magazine called the post office the “graveyard of negro talent,” referring to the highly educated African-Americans who took jobs at the post office because they could not find work elsewhere. In 1940, 21 percent of the African-Americans who worked for the post office had a college education, compared to the 5 percent of the black population as a whole who had college degrees, Rubio said.

The fight to fix disparities between black and white postal workers started in Durham with George Booth Smith, the city’s first black letter carrier.

Smith applied to be a letter carrier in the 1950s but was denied the job, despite holding a master’s degree in library science from North Carolina Central University. He eventually arranged a meeting with the Postmaster General in Washington, D.C., and orders were sent back to Durham to hire Booth.

Jimmy Mainor, an introductory speaker at Sunday’s event who worked for the Durham post office from 1973 to 2010, said Booth’s actions represented the city of Durham by standing up for what was right and by creating a diverse work force.

Rubio researched this work force back to the 1800s. From 1802 to 1865, there was a federal law that only allowed “free white persons” to deliver mail, he said.

Groups like the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees, a historically black labor union, facilitated a tradition of protests for better working conditions.

Such protests eventually led to a nationwide strike in 1970. About 200,000 postal workers took part in the strike, which lasted eight days. President Richard Nixon even called on the National Guard to move mail in New York City. Eventually, postal workers earned collective bargaining rights and better wages.

“Today, more than ever before, we have more diversity, equality and promotions at the post office,” Rubio said. He added that post office employees today are 21 percent African-American, 8 percent Hispanic, 8 percent Asian and 37 percent women.

“It pays decent, and I get to interact with people, which is important to me,” said Joyce Campbell, a window clerk who has worked at the downtown Durham post office for 23 years.

But despite the advancements for black postal workers, some say the fight is not finished.

“In 38 years, I’ve seen a lot of things that are unfair,” said Jackie Foster, another postal worker who was honored at the event. She spoke of management training programs that would not choose black postal workers and emphasized the importance of unions.

“I saw it as an opportunity,” Foster said. “I’m telling the ones who are not in the union now to get in the union and fight for their jobs and for their future.”